This has been ported over to my GitHub site and is not longer being maintained here. For any issues, comments or updates head here.

What is that thing they call a PDF?

The Portable Document Format (PDF) is an old format ... it was created by Adobe back in 1993 as an open standard but wasn't officially released as an open standard (SIO 32000-1) until 2008 - right @nullandnull ? I can't take credit for the nickname that I call it today, Payload Delivery Format, but I think it's clever and applicable enough to mention. I did a lot of painful reading through the PDF specifications in the past and if you happen to do the same I'm sure you'll also have a lot of "hm, that's interesting" thoughts as well as many "wtf, why?" thoughts. I truly encourage you to go out and do the same... it's a great way to learn about the internals of something, what to expect and what would be abnormal. The PDF has become a defacto for transferring files, presentations, whitepapers etc.<rant> How about we stop releasing research/whitepapers about PDF 0-days/exploits via a PDF file... seems a bit backwards</rant>

We've all had those instances where you wonder if that file is malicious or benign ... do you trust the sender or was it downloaded from the Internet? Do you open it or not? We might be a bit more paranoid than most people when it comes to this type of thing and but since they're so common they're still a reliable means for a delivery method by malicious actors. As the PDF contains many 'features', these features often turn into 'vulnerabilities' (Do we really need to embed an exe into our PDF? or play a SWF game?). Good thing it doesn't contain any vulnerabilities, right? (to be fair, the sandboxed versions and other security controls these days have helped significantly)

What does a PDF consist of?

In its most basic format, a PDF consists of four components: header, body, cross-reference table (Xref) and trailer:

(sick M$ Paint skillz, I know)

If we create a simple PDF (this example only contains a single word in it) we can see a better idea of the contents we'd expect to see:

What else is out there?

Since PDF files are so common these days there's no shortage of tools to

rip them apart and analyze them. Some of the information contained in

this post and within the code I'm releasing may be an overlap of others

out there but that's mainly because the results of our research produced

similar results or our minds think alike...I'm not going to touch on

every tool out there but there are some that are worth mentioning as I

either still use them in my analysis process or some of their

functionality/lack of functionality is what sparked me to write AnalyzePDF.

By mentioning the tools below my intentions aren't to downplay them

and/or their ability to analyze PDF's but rather helping to show reasons

I ended up doing what I did.

pdfid/pdf-parser

Didier Stevens

created some of the first analysis tools in this space, which I'm sure

you're already aware of. Since they're bundled into distros like

BackTrack/REMnux

already they seem like good candidates to leverage for this task. Why

recreate something if it's already out there? Like some of the other

tools, it parses the file structure and presents the data to you... but

it's up to you to be able to interpret that data. Because these tools

are commonly available on distros and get the job done I decided they

were the best to wrap around.

Did you know that pdfid has a lot more capability/features that most aren't aware of? If you run it with the (-h) switch you'll see some other useful options such as the (-e) which display extra information. Of particular note here is the mention of "%%EOF", "After last %%EOF", create/mod dates and the entropy calculations. During my data gathering I encountered a few hiccups that I hadn't previously experienced. This is expected as I was testing a large data set of who knows what kind of PDF's. Again, I'm not noting these to put down anyone's tools but I feel it's important to be aware of what the capabilities and limitations of something are - and also in case anyone else runs into something similar so they have a reference. Because of some of these, I am including a slightly modified version of pdfid as well. I haven't tested if the newer version fixed anything so I'd rather give the files that I know work with it for everyone.

Did you know that pdfid has a lot more capability/features that most aren't aware of? If you run it with the (-h) switch you'll see some other useful options such as the (-e) which display extra information. Of particular note here is the mention of "%%EOF", "After last %%EOF", create/mod dates and the entropy calculations. During my data gathering I encountered a few hiccups that I hadn't previously experienced. This is expected as I was testing a large data set of who knows what kind of PDF's. Again, I'm not noting these to put down anyone's tools but I feel it's important to be aware of what the capabilities and limitations of something are - and also in case anyone else runs into something similar so they have a reference. Because of some of these, I am including a slightly modified version of pdfid as well. I haven't tested if the newer version fixed anything so I'd rather give the files that I know work with it for everyone.

- I first experienced a similar error as mentioned here when using the (-e) option on a few files (e.g. - cbf76a32de0738fea7073b3d4b3f1d60). It appears it doesn't count multiple '%%EOF's since if the '%%EOF' is the last thing in the file without a '/r' or '/n' behind it, it doesn't seem to count it.

- I've had cases where the '/Pages' count was incorrect - there were (15) PDF's that showed '0' pages during my tests. One way I tried to get around this was to use the (-a) option and test between the '/Page' and '/Pages/ values. (e.g. - ac0487e8eae9b2323d4304eaa4a2fdfce4c94131)

- There were times when the number of characters after the last '%%EOF' were incorrect

- Won't flag on JavaScript if it's written like "<script contentType="application/x-javascript">" (e.g - cbf76a32de0738fea7073b3d4b3f1d60) :

peepdf

Peepdf has gone through some great development over the course of me

using it and definitely provides some great features to aid in your

analysis process. It has some intelligence built into it to flag on

things and also allows one to decode things like JavaScript from the

current shell. Even though it has a batch/automated mode to it, it still feels

like more of a tool that I want to use to analyze a single PDF at a time

and dig deep into the files internals.

- Originally, this tool didn't look match keywords if they had spaces after them but it was a quick and easy fix... glad this testing could help improve another users work.

PDFStreamDumper

PDFStreamDumper is a great tool with many sweet features but it has its

uses and limitations like all things. It's a GUI and built for analysis

on Windows systems which is fine but it's power comes from analyzing a

single PDF at a time - and again, it's still mostly a manual process.

pdfxray/pdfxray_lite

Pdfxray was originally an online

tool but Brandon created a lite version so it could be included in

REMnux (used to be publicly accessible but at the time of writing this

looks like that might have changed). If you look back at some of Brandon's

work historically he's also done a lot in this space as well and since I

encountered some issues with other tools and noticed he did as well in

the past I know he's definitely dug deep and used that knowledge for his

tools. Pdfxray_lite has the ability to query VirusTotal for the file's

hash and produce a nice HTML report of the files structure - which is

great if you want to include that into an overall report but again this requires the user to interpret the parsed data

pdfcop

Pdfcop is part of the Origami framework. There're some really cool tools

within this framework but I liked the idea of analyzing a PDF file and

alerting on badness. This particular tool in the framework has that

ability, however, I noticed that if it flagged on one cause then it

wouldn't continue analyzing the rest of the file for other things of

interest (e.g. - I've had it close the file our right away if there was an invalid Xref without looking at anything else. This is because PDF's are read from the bottom up meaning their Xref tables are first read in order to determine where to go next). I can see the argument of saying why continue to analyze the

file if it already was flagged bad but I feel like that's too much of

tunnel vision for me. I personally prefer to know more than

less...especially if I want to do trending/stats/analytics.

So why create something new?

While there are a wealth of PDF analysis tools these days, there was a

noticeable gap of tools that have some intelligence built into them in

order to help automate certain checks or alert on badness. In fairness, some (try to) detect exploits based on keywords or flag suspicious objects based on their contents/names but that's generally the extent of it. I use a lot

of those above mentioned tools when I'm in the situation where I'm

handed a file and someone wants to know if it's malicious or not... but

what about when I'm not around? What if I'm focused/dedicated to

something else at the moment? What if there's wayyyy too many files for

me to manually go through each one? Those are the kinds of questions I

had to address and as a result I felt I needed to create something new.

Not necessarily write something from scratch... I mean why waste that

time if I can leverage other things out there and tweak them to fit my

needs?

Thought Process

What do people typically do when trying to determine if a PDF file is benign or malicious? Maybe scan it with A/V and hope something triggers, run it through a sandbox and hope the right conditions are met to trigger or take them one at a time through one of the above mentioned tools? They're all fine work flows but what if you discover something unique or come across it enough times to create a signature/rule out of so you can trigger on it in the future? We tend to have a lot to remember so doing the analysis one offs may result in us forgetting something that we previously discovered. Additionally, this doesn't scale too great in the sense that everyone on your team might not have the same knowledge that you do... so we need some consistency/intelligence built in to try and compensate for these things.<

I felt it was better to use the characteristics of a malicious file

(either known or observed from combinations of within malicious files)

to eval what would indicate a malicious file. Instead of just adding

points for every questionable attribute observed. e.g. - instead of

adding a point for being a one page PDF, make a condition to say if you

see an invalid xref and a one page PDF then give it a score of X. This

makes the conditions more accurate in my eyes; since, for example:

- A single paged PDF by itself isn't malicious but if it also contains other things of question then it should have a heavier weight of being malicious.

- Another example is JavaScript within a PDF. While statistics show JavaScript within a PDF are a high indicator that it's malicious, there're still legitimate reasons for JavaScript to be within a PDF (e.g. - to calculate a purchase order form or verify that you correctly entered all the required information the PDF requires).

Gathering Stats

At the time I was performing my PDF research and determining how I

wanted to tackle this task I wasn't really aware of machine learning. I

feel this would be a better path to take in the future but the way I

gathered my stats/data was in a similar (less automated/cool AI) way.

There's no shortage of PDF's out there which is good for us as it can

help us to determine what's normal, malicious, or questionable and

leverage that intelligence within a tool.

If you need some PDF's to gather some stats on, contagio has a pretty big bundle to help get you started. Another resource is Govdocs from Digital Corpora ... or a simple Google dork.

Note : Spidering/downloading these will give you files but they still need to be classified as good/bad for initial testing). Be aware that you're going to come across files that someone may mark as good but it actually shows signs of badness... always interesting to detect these types of things during testing!

Stat Gathering Process

So now that I have a large set of files, what do I do now? I can't just rely on their file extensions or someone else saying they're malicious or benign so how about something like this:- Verify it's a PDF file.

- When reading through the PDF specs I noticed that the PDF header can be within the first 1024 bytes of the file as stated in ""3.4.1, 'File Header' of Appendix H - ' Acrobat viewers require only that the header appear somewhere within the first 1024 bytes of the file.'"... that's a long way down compared to the traditional header which is usually right in the beginning of a file. So what's that mean for us? Well if we rely solely on something like file or TRiD they _might_ not properly identify/classify a PDF that has the header that far into the file as most only look within the first 8 bytes (unfair example is from corkami). We can compensate for this within our code/create a YARA rule etc.... you don't believe me you say? Fair enough, I don't believe things unless I try them myself either:

- Get rid of duplicates (based on SHA256 hash) for both files in the same category (clean vs. dirty) then again via the entire data set afterwards to make sure there're no duplicates between the clean and dirty sets.

- Run pdfid & pdfinfo over the file to parse out their data.

- These two are already included in REMnux so I leveraged them. You can modify them to other tools but this made it flexible for me and I knew the tool would work when run on this distro; pdfinfo parsed some of the data better during tests so getting the best of both of them seemed like the best approach.

- Run scans for low hanging fruit/know badness with local A/V||YARA Now that we have a more accurate data set classified:

- Are all PDFs classified as benign really benign?

- Are all PDFs classified as malicious really malicious?

The file to the left is properly identified as a PDF file but when I

created a copy of it and modified it so the header was a bit lower, the

tools failed. The PDF on the right is still in accordance with the PDF

specs and PDF viewers will still open it (as shown)... so this needs to

be taken into consideration.

Stats

Files analyzed (no duplicates found between clean & dirty):| Class | Type | Count |

|---|---|---|

| Dirty | Pre-Dup | 22,342 |

| Dirty | Post-Dup | 11,147 |

| Clean | Pre-Dup | 2,530 |

| Dirty | Post-Dup | 2,529 |

| Total Files Analyzed: | 13,676 | |

I've collected more than enough data to put together a paper or presentation but I feel that's been played out already so if you want more than what's outlined here just ping me. Instead of dragging this post on for a while showing each and every stat that was pulled I feel it might be more useful to show a high level comparison of what was detected the most in each set and some anomalies.

Ah-Ha's

- None of the clean files had incorrect file headers/versions

- There wasn't a single keyword/attribute parsed from the clean files that covered more than 4.55% of it's entire data set class. This helps show the uniqueness of these files vs. malicious actors reusing things.

- The dates within the clean files were generally unique while the date fields on the dirty files were more clustered together - again, reuse?

- None of the values for the keywords/attributes of the clean files were flagged as trying to be obfuscated by pdfid

- Clean files never had '/Colors > 2^24' above 0 while some dirty files did

- Rarely did a clean file have a high count of JavaScript in it while dirty files ranged from 5-149 occurrences per file

- '/JBIG2Decode' was never above '0' in any clean file

- '/Launch' wasn't used much in either of the data sets but still more common in the dirty ones

- Dirty files have far more characters after the last %%EOF (starting from 300+ characters is a good check)

- Single page PDF's have a higher likelihood of being malicious - no duh

- '/OpenAction' is far more common in malicious files

YARA signatures

I've also included some PDF YARA rules that I've created as a separate file so you can use those to get started. YARA isn't really required but I'm making it that way for the time being because it's helpful... so I have the default rules location pointing to REMnux's copy of MACB's rules unless otherwise specified.Clean data set:

Dirty data set:

Signatures that triggered across both data sets:

Cool... so we know we have some rules that work well and others that might need adjusting, but they still help!

What to look for

So we have some data to go off of... what are some additional things we can take away from all of this and incorporate into our analysis tool so we don't forget about them and/or stop repetitive steps?

- Header

- In addition to being after the first 8 bytes I found it useful to look at the specific version within the header. This should normally look like "%PDF-M.N." where M.N is the Major/Minor version .. however, the above mentioned 'low header' needs to be looked for as well.

Knowing this we can look for invalid PDF version numbers or digging deeper we can correlate the PDF's features/elements to the version number and flag on mismatches. Here're some examples of what I mean, and more reasons why reading those dry specs are useful: - If FlateDecode was introduced in v1.2 then it shouldn't be in any version below

- If JavaScript and EmbeddedFiles were introduced in v1.3 then they shouldn't be in any version below

- If JBIG2 was introduced in v1.4 then it shouldn't be in any version below

- Body

- This is where all of the data is (supposed to be) stored; objects (strings, names, streams, images etc.). So what kinds of semi-intelligent things can we do here?

- Look for object/stream mismatches. e.g - Indirect Objects must be represented by 'obj' and 'endobj' so if the number of 'obj' is different than the number of 'endobj' mentions then it might be something of interest

- Are there any questionable features/elements within the PDF?

- JavaScript doesn't immediately make the file malicious as mentioned earlier, however, it's found in ~90% of malicious PDF's based on others and my own research.

- '/RichMedia' - indicates the use of Flash (could be leveraged for heap sprays)

- '/AA', '/OpenAction', '/AcroForm' - indicate that an automatic action is to be performed (often used to execute JavaScript)

- '/JBIG2Decode', '/Colors' - could indicate the use of vulnerable filters; Based on the data above maybe we should look for colors with a value greater than 2^24

- '/Launch', '/URL', '/Action', '/F', '/GoToE', '/GoToR' - opening external programs, places to visit and redirection games

- Obfuscation

- Multiple filters ('/FlateDecode', '/ASCIIHexDecode', '/ASCII85Decode', '/LZWDecode', '/RunLengthDecode')

- The streams within a PDF file may have filters applied to them (usually for compressing/encoding the data). While this is common, it's not common within benign PDF files to have multiple filters applied. This behavior is commonly associated with malicious files to try and thwart A/V detection by making them work harder.

- Separating code over multiple objects

- Placing code in places it shouldn't be (e.g. - Author, Keywords etc.)

- White space randomization

- Comment randomization

- Variable name randomization

- String randomization

- Function name randomization

- Integer obfuscation

- Block randomization

- Any suspicious keywords that could mean something malicious when seen with others?

- eval, array, String.fromCharCode, getAnnots, getPageNumWords, getPageNthWords, this.info, unescape, %u9090

- Xref The first object has an ID 0 and always contains one entry with generation number 65535. This is at the head of the list of free objects (note the letter ‘f’ that means free). The last object in the cross reference table uses the generation number 0.

- Trailer

- Provides the offset of the Xref (startxref)

- Contains the EOF, which is supposed to be a single line with "%%EOF" to mark the end of the trailer/document. Each trailer will be terminated by these characters and should also contain the '/Prev' entry which will point to the previous Xref.

- Any updates to the PDF usually result in appending additional elements to the end of the file

This makes it pretty easy to determine PDF's with multiple updates or additional characters after what's supposed to be the EOF - Misc.

- Creation dates (both format and if a particular one is known to be used)

- Title

- Author

- Producer

- Creator

- Page count

Translation please? Take a look a the following Xref:

Knowing how it's supposed to look we can search for Xrefs that don't adhere to this structure.

The Code

So what now? We have plenty of data to go on - some previously known, but some extremely new and helpful. It's one thing to know that most files with JavaScript or that are (1) page have a higher tendency of being malicious... but what about some of the other characteristics of these files? By themselves, a single keyword/attribute might not stick out that much but what happens when you start to combine them together? Welp, hang on because we're going to put this all together.File Identification

In order to account for the header issue, I decided the tool itself would look within the first 1024 bytes instead of relying on other file identification tools:Wrap pdfinfo

Through my testing I found this tool to be more reliable in some areas as opposed to pdfid such as:- Determining if there're any Xref errors produced when trying to read the PDF

- Look for any unterminated hex strings etc.

- Detecting EOF errors

Wrap pdfid

- Read the header. *pdfid will show exactly what's there and not try to convert it*

- _attempt_ to determine the number of pages

- Look for object/stream mismatches

- Not only look for JavaScript but also determine if there's an abnormally high amount

- Look for other suspicious/commonly used elements for malicious purposes (AcroForm, OpenAction, AdditionalAction, Launch, Embedded files etc.)

- Look for data after EOF

- Calculate a few different entropy scores

Next, perform some automagical checks and hold on to the results for later calculations.

And here's another YARA rule with that section highlighted for those who aren't sure what I'm talking about:

If the (-m) option is supplied then if _any_ YARA rule triggers on the PDF file it will be moved to another directory of your choosing. This is important to note because one of your rules may hit on the file but it may not be displayed in the output, especially if it doesn't have a weight field.

Once the analysis has completed the calculation process starts. This is two phase -

Scan with YARA

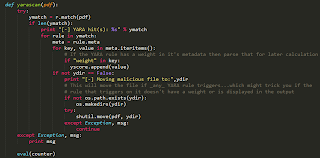

While there are some pre-populated conditions that score a ranking built into the tool already, the ability to add/modify your own is extremely easy. Additionally, since I'm a big fan of YARA I incorporated it into this as well. There're many benefits of this such as being able to write a rule for header evasion, version number mismatching to elements or even flagging on known malicious authors or producers. The biggest strength, however, is the ability to add a 'weight' field in the meta section of the YARA rules. What this does is allow the user to determine how good of a rule it is and if the rule triggers on the PDF, then hold on to its weighted value and incorporate it later in the overall calculation process which might increase it's maliciousness score. Here's what the YARA parsing looks like when checking the meta field:And here's another YARA rule with that section highlighted for those who aren't sure what I'm talking about:

If the (-m) option is supplied then if _any_ YARA rule triggers on the PDF file it will be moved to another directory of your choosing. This is important to note because one of your rules may hit on the file but it may not be displayed in the output, especially if it doesn't have a weight field.

Once the analysis has completed the calculation process starts. This is two phase -

- Anything noted from pdfino and pdfid are evaluated against some pre-determined combinations I configured. These are easy enough to modify as needed but they've been very reliable in my testing...but hey, things change! Instead of moving on once one of the combination sets is met I allow the scoring to go through each one and add the additional points to the overall score, if warranted. This allows several 'smaller' things to bundle up into something of interest rather than passing them up individually.

- Any YARA rule that triggered on the PDF file has it's weighted value parsed from the rule and added to the overall score. This helps bump up a files score or immediately flag it as suspicious if you have a rule you really want to alert on.

So what's it look like in action? Here's a picture I tweeted a little while back of it analyzing a PDF exploiting CVE-2013-0640 :

Download

I've had this code for quite a while and haven't gotten around to

writing up a post to release it with but after reading a former coworkers blog post last

night I realized it was time to just write something up and get this

out there as there are still people asking for something that employs

some of the capabilities (e.g. - weight ranking). Is this 100% right

all the time? No... let's be real. I've come across situations where a

file that was benign was flagged as malicious based on its

characteristics and that's going to happen from time to time. Not all

PDF creators adhere to the required specifications and some users think

it's fun to embed or add things to PDF's when it's not necessary.

What this helps to do is give a higher ranking to files that require closer attention or help someone determine if they should open a file

right away vs. send it to someone else for analysis (e.g. - deploy

something like this on a web server somewhere and let the user upload

their questionable file to is and get back a "yes it's ok -or- no,

sending it for analysis".

AnalyzePDF can be downloaded on my github

AnalyzePDF can be downloaded on my github

Further Reading

- Research papers (one | two | three) [PDF]

- PDFTricks

- PDF Overview